The doctor finally brought it over in what looked like a very sophisticated cat carrier. Of course, at first Lew had no idea what was in the grayish box with its LCD screen and blinking lights, and just stood frowning blearily at this unexpected morning visitor in his doorway. You’ve got the wrong apartment, he almost said, belatedly recognizing Dr. Velez from the accident. “How did you get in here?” he came out with instead.

“Your neighbor let me in,” she said, sounding almost apologetic. “I thought about buzzing up, but I knew it might just go to your phone again, and you never seem to answer that.”

“Your neighbor let me in,” she said, sounding almost apologetic. “I thought about buzzing up, but I knew it might just go to your phone again, and you never seem to answer that.”

“Sorry,” he muttered. He glanced down the hall as though he might find that easygoing neighbor there to accuse. “So what’s up?”

“Can I come in?”

He sighed, like he was in the middle of something, instead of sitting in front of his TV at ten in the morning. He looked briefly at the hallway behind him, and finally shook his head and stood aside.

It was then that he noticed the cat carrier, as she bent slightly at the knees to pick it up and pushed past him in the hall with the box balanced against her hips. It seemed, from her effort, to weigh a fair bit. “What the hell is that?”

“It’s why I’m here.”

No one but him had ever been inside the apartment, and with her entry he was forced to see it from her perspective. Kind of a shithole, or rather, a decent apartment occupied by a shitheel. A shitheel shithole. Flattened boxes behind the door in the hall, left from when he’d moved in six weeks ago. He kept meaning to take them out, but who gave a shit, right? More boxes, unpacked, in the living room. Bare beige walls. The steamer trunk that served as a coffee table overrun with dishes, beer cans, stacks of mail, including some of the preposterous medical bills for which Velez herself was partially responsible. Hopefully she wouldn’t look in the kitchen.

“New apartment?” she asked.

“Something like that.” He gestured toward the couch half-heartedly. Carefully she set down the carrier on the floor by the coffee table, turned and sat on the edge of the cushions.

“How’ve you been?”

Fucking awesome. Living that bachelor life. Now that my wife and son are dead, I party all night, sleep all day. Sometimes in between I dare myself to cut my wrists, but so far the beer’s keeping that in check.

“Fine,” he said.

“Depressed?”

“What gave you that idea?” He went to the armchair that faced the couch, threw the dirty clothes off of it and onto the floor, and slumped down into its yellow embrace.

“Female intuition?”

“No, I’m not depressed. Everything’s fucking grand.” It was the worst year of his life, and not just the worst year so far. There would never be a worse year.

“Are you working?”

“Some.”

“You’re a … graphic designer, is that right?”

“Yep. My office, right there.” He waved at the computer on the desk.

“How’s business?”

“Keeps me going.” He rose. “You want a beer? I got Bud Light or Bud Light.”

She extended a hand to stop him on his way to the fridge. “Wait, please. Before you start drinking … there’s something you need to see.”

“Whatever’s in the cat carrier, I guess?” He frowned at the box by his feet. “What is in that thing? Is it actually a cat? Is that the idea here, like, get Lew something to take care of so he doesn’t off himself?” He nudged it with his toe. There were readouts on its screen, wave forms zigzagging in green light. “Is the cat sick or something?”

“It’s not a cat. Please, sit down and I’ll explain.” She gestured at the couch beside her. Inexplicably perturbed, Lew sat.

Velez began clearing space on the steamer trunk, transferring magazines to the floor, stacking dishes, pushing cans aside. Impatiently, Lew said, “Here,” and began helping her, taking the dishes to the kitchen, putting the cans in the recycling. Then he sat back down. She’d succeeded to that degree, he reflected. She’d made him clean up his living room.

“There. We good?”

“Can we turn off the TV, please?”

“All right, but you’re going to make me miss the second quarter of the Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl Semifinal game. It’s on your head.”

In the ensuing silence he could hear someone talking on their phone in the parking lot and the hum of the swamp cooler in the hall. “I’m here to talk to you about your son. Jack.”

“I’m not looking for a counselor,” he said brusquely.

“Maybe you should be. But that’s not why I’m here.”

“What then? What is it, some kind of permission you need for his organs again? You need me to sign so you can sell off his heart or lungs or his little fucking toes?” Angry tears were in his eyes. “And what’s in the fucking box?”

Just an accident. One of thousands. A car gets a flat on the interstate, spins out of control. The cars around it try to avoid it, and they too collide. You wake up to your wife and son dead beside you, half the car crushed in the press. He squeezed his eyes shut tight, wishing he could shut his memory off the same way. Leila had died instantly of brain trauma, Jack on the way to the hospital.

“During the accident, Jack’s body was catastrophically injured.” God, what a phrase. “His rib cage was crushed, his limbs … irretrievably injured.”

“Why are you telling me this?” he groaned.

“With your permission, he was taken to surgery for organ donation.”

Velez herself would barely meet his eye, instead fixing her gaze on a readout on the carrier. “Here’s where it gets a bit complicated. The surgeon working on Jack was – is – something of a pioneer in cryogenics. He had been looking for a patient like Jack for some time. A infant, very newly deceased, with a specific grouping of injuries. He believed, on the basis of his research, that certain properties of an infant’s cells and brain would allow resuscitation of the brain, where it had failed on more mature specimens.”

Lew’s own brain seemed to be frozen. He just kept staring at her incredulously. “You’re saying … he’s not dead?”

Finally she met his eye. She looked frightened, and why? But then she nodded, once. “That’s correct.” When this met with a shocked silence, she went on, “Dr. Bettencourt was able to electrically restart Jack’s brain. He then placed him in a life-support system and nutrient bath, thereby keeping him alive. He is alive, Lew.”

“Where?” he whispered. “Where is he?”

Her eyes slid uneasily to the carrier on the table. He looked at it in confusion. “What are you saying? He’s inside this thing?”

She nodded. There was a sheen of sweat on her forehead, though it was cool in the apartment. “I came here to show him to you. I wasn’t positive you would come to the hospital, and I felt strongly you needed to see him for yourself. Dr. Bettencourt took some persuading, but he had this unit available for Jack’s life support, and finally –”

“Why would I not want to see him?” Lew exclaimed. “And how in the fuck did you not tell me before? He’s alive?! He’s been alive this whole time? That’s sick, that’s –”

“Sit down, please. Please, Lew.” Her hand was extended like a shield. “You don’t understand. He was catastrophically injured.”

“Show him to me,” he commanded. “Show him to me.”

She nodded, biting her lip. She turned the carrier slightly toward him and tapped some commands on the LCD screen. It flashed. The front of the box opened, each side sliding back from the center line smoothly and mechanically.

His first thought: It’s a doll’s head.

His second: Why is it upside down?

His third, repeating: It’s not a doll’s head, it’s not a doll’s head, it’s not a doll’s head…

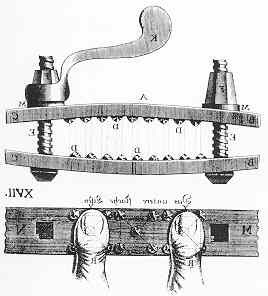

No, it was not a doll’s head. It was Jack’s head, cradled upside-down in the box’s softly lit heart by a score of foam-padded struts, silvery screws and glinting needles. His little neck was mercifully encircled by a two-inch-wide silver collar, above which extended a wrist-thick chock of vined and multicolored tubes, wires and conduits. Utterly horrified, not thinking at all, Lew sank to his knees, until he could look at that darling, serene face in its monstrous container.

God, it was, it was him. Those big pink baby cheeks, that pouty mouth hanging open, his golden hair. His eyes were closed, but between his so-fine brows Lew could see that Jack had a bit of a rash, the skin raised pink against the pale. Lew watched closely, realized with numb horror that his son’s nostrils were flaring slightly with each breath.

“You may be wondering why he’s upside-down,” Velez was saying. “Basically it’s to relieve downward pressure on all the, uh, connectors, the veins, arteries, nerves and whatnot. You can understand, this is extremely fine work. In fact most of the connectors are designed by AIs and created at a nanomolecular scale, it has to be that precise…”

“What did you do?” he interrupted hoarsely, finally tearing his gaze from that hideous, adored visage hanging in its box like the world’s most perverse diorama. Slowly he stood up, hands at his sides.

Velez saw the look on his face. “Listen, Lew. Listen to me. He doesn’t know what’s happened to him. Bettencourt has created a direct interface with Jack’s spinal cord that simulates all the sensations of having a body, modeled after other infants. He thinks he’s in a cradle, wiggling his arms and legs around, getting stronger. As he grows – and he will grow, every nutrient and hormone he needs is provided for – those sensations will become more complex. Eventually, he can either be transplanted to a suitable body, when and if one becomes available, or outfitted with an android body for movement in the real world. Or he can continue living virtually, remaining in his cradle and experiencing the world virtually.

“But the point is, he is alive. He thinks and feels, and he’s going to need real human relationships. He’s going to need a father. He –”

“What did you do?!” he shouted. His rage exploded from him, white hot and blinding, uncontrollable. “You fucking monster! Jesus Christ, what did you do, I should cut off your head, you sadistic fuck, then burn your goddamn laboratory to the ground, I swear to God, I’ll –”

He stopped mid-sentence, hearing the thin wail just below him. He knew that cry, and it twisted around his heart like a thorny vine.

“You woke him,” Velez said quietly, reproachfully, coming around the couch to place a hand into the carrier. “Shhh, baby, it’s okay, it’s okay.”

Slowly, knowing he was defeated, he knelt again on the carpet. Jack was crying, tears streaming downward from his eyes across his forehead and into his hair. Velez was trying to offer him a pacifier, but he wasn’t taking it.

“Here. You try.”

Numbly Lew took the pacifier. After a moment he reached out with it and held it lightly at his son’s lips. “Jack,” he said. Jack looked at him, stopped screaming, and took the pacifier.

Did Jack recognize him? Lew thought he did. Gently he reached out a finger and touched his son’s cheek. It was as soft as the day he was born.